Friday, December 01, 2006

Poisoning the Workers' Beer

Blue collar radiation exposure lacks cachet for Fourth Estate

The media stir caused by the recent poisoning death of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko in London recently has focused attention on Polonium-210, the radioactive isotope thought to have killed him. The chief suspect in the case is Russian President Vladimir Putin, who Litvinenko accused of orchestrating his assassination shortly before he died.

The story of Litvinenko's mysterious death has all the ingredients of a bestselling thriller worthy of Ian Fleming or Tom Clancy. The quantity of Polonium-210 used to kill the ex-spy was the size of a grain of sand. The poisoning has made headline worldwide. But the potential radioactive contamination of large volumes of beer at the Anheuser-Busch brewery in St. Louis in 1988 received far less scrutiny.

Polonium-210 was also the subject of concern in that case. Government inspectors determined that static air eliminators used on production lines at the brewery were found to be leaking the nuclear material for an unspecified length of time. But when the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported the problem it downplayed the health risks to workers and consumers and misrepresented where the contamination took place.

Radioactive leaks also occurred at other St. Louis area companies, including McDonnell Douglas Corp., which sent some of its workers home after the leaks were discovered. 3M Corp. of Minneapolis produced the faulty devices that caused the hazard.

The Post-Dispatch first broached the subject on Saturday Feb. 6, 1988. In its initial story by staffers Peter Hernon and Theresa Tighe, the newspaper reported leaks in laboratories at McDonnell-Douglas. Three days later, a page one story by Christine Bertelsen reported on the radioactive contamination at Anheuser-Busch and elsewhere. The second paragraph of that story said: "Officials at Anheuser-Busch insisted that 'absolutely no health hazard existed.'" The story goes on to quote a brewery spokesman denying any risk: "There was no effect whatsoever on product quality. ... No plants were shut down."

Indeed, work continued uninterrupted at the brewery and unlike McDonnell-Douglas no workers at Anheuser-Busch were sent home or tested.

Bertelsen's story said that "areas contaminated with low-level emissions were cleaned last week." But the story gave no indication of where the leaks occurred. After the front-page coverage on Feb. 9, 1988, the story all but died in St. Louis. Three days later, on Feb. 12, 1988, then-Post reporter Joan Bray filed a story buried on page 4-C with the obituaries that reported further recalls of faulty 3M static air eliminators. Bray inaccurately reported that "laboratories where the devices were used at Anheuser-Busch ... have been decontaminated."

The faulty static air eliminators weren't used in laboratories, however. Instead, the devices were used in the production process to dust the inside of bottle caps before they were placed on the full bottles of beer coming out of the fillers.

Obviously, radioactive isotopes leaking at a point in the assembly lines where the filled beer bottles were capped posed a greater risk to consumers and workers then if the devices had merely leaked in laboratories. Whether the ceramic coating surrounding the radioactive pellets would lessen the risk of exposure wasn't cited.

I worked as a beer bottler at the Anheuser-Busch brewery in St. Louis in 1988. When I learned that the leaks occurred on the bottling units and not in laboratories as reported by the Post-Dispatch, I called reporter Christine Bertelsen and informed her.

She didn't follow up on my tip.

More than two years later, Bertelsen did, however, report that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission was seeking to fine 3M $160,000 over the defective devices. Her story wrongly identified the radioactive isotope that had leaked out of the devices as "polonium-20."

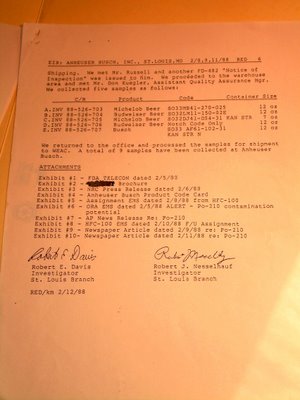

In March 1988, the NRC denied my Freedom of Information request on the radioactive leaks at Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis, but the Food and Drug Administration released a partially redacted report of its limited inspection.

The inspection was categorized by FDA as "limited" because it did not independently test all of the suspected devices but relied largely on information provided by the NRC and Anheuser-Busch. Moreover, by blacking out the unit numbers in its report the FDA made it difficult, if not impossible, to determine which batches of beer may have been contaminated. Nonetheless, it is clear from the report that more than one bottle unit had operated with faulty static air eliminators that spewed Polonium-210. The copy of the report indicates that the FDA uncovered another bottle unit had been contaminated, which was overlooked by the NRC and Anheuser-Busch.

The FDA report says that Knut Heise, then-associate general counsel for Anheuser-Busch, "admitted that a mistake was made," by the company when it failed to initially identify the other faulty device that leaked Polonium-210. Led by Anheuser-Busch quality assurance employees, the FDA reported that it took samples of the various brands of Anheuser-Busch products for testing. The results of those tests are not contained in the report.

St. Louis-based FDA investigators Robert E. Davis and Robert Nesselhauf signed the report dated Feb. 12, 1988. The random samples taken would only represented a small fraction of the beer that could have potentially been contaminated.

Cleaning crews washed the contaminated surfaces down with water and the walls and columns were repainted. Work went on as usual and beer continued to be bottled, packaged and shipped 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Since then, of course, many Anheuser-Busch employees have died of cancer, and ingesting or breathing Polonium-210 can cause cancer. But no epidemiological studies have ever been conducted to determine whether a correlation exists that would link the leaks to cancer clusters in the work place.

Looking back on it, it's almost like the radioactive incident at the St. Louis brewery in 1988 never happened. Almost.